The history of genetics is the history of promises. This statement is attributed to historian Nathaniel Comfort in a recent diatribe by David Dobbs, which was posted at Buzzfeed. The delightfully pessimistic Dobbs essay is especially hard on genetic testing, which took a further beating this week in the New England Journal of Medicine when it was reported that different laboratories offer wildly different interpretations of the same genetic tests. There seems to be a consensus around the notion that most genetic testing for predisposition to common diseases is "not ready for prime time", and yet the tsunami of false positive claims continues in the literature unabated, and each time with recommendations for more population screening.

This press release reports on a 2013 study by Ziki et al in the American Journal of Cardiology, which describes a genetic variation that is linked to increased levels of triglycerides, and which the authors assert is more common than previously believed and disproportionately affects people of African ancestry.

"The finding offers a clue as to why Africans and people of African descent have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes compared to many other populations, says the study's senior author, Dr. Ronald Crystal, chairman of genetic medicine at Weill Cornell. African Americans with the variant had, on average, 52 percent higher triglyceride levels compared with blacks in the study who did not have the variant."

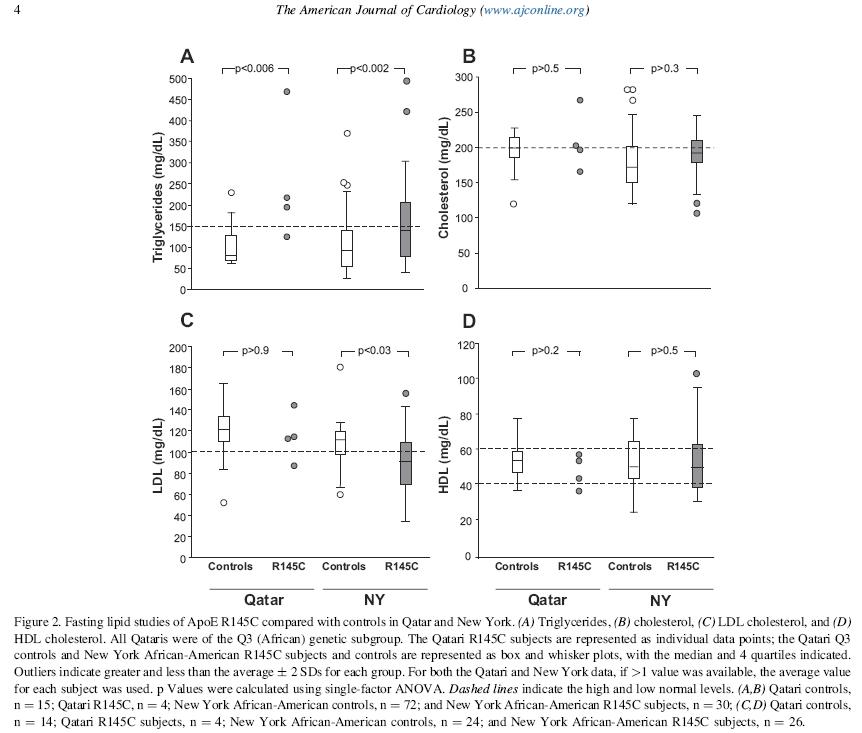

But have a look at Figure 2 from Ziki et al:

This press release reports on a 2013 study by Ziki et al in the American Journal of Cardiology, which describes a genetic variation that is linked to increased levels of triglycerides, and which the authors assert is more common than previously believed and disproportionately affects people of African ancestry.

"The finding offers a clue as to why Africans and people of African descent have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes compared to many other populations, says the study's senior author, Dr. Ronald Crystal, chairman of genetic medicine at Weill Cornell. African Americans with the variant had, on average, 52 percent higher triglyceride levels compared with blacks in the study who did not have the variant."

But have a look at Figure 2 from Ziki et al:

You can immediately see that the whiz-bang result here is actually due to one or two outliers in Panel A. In the Qatar sample in panel A, there is one individual with the mutation who has high triglycerides. In the NY sample in Panel A, the distribution in the affected individuals is shifted up a bit, but is completely overlapping, except for 2 individuals. When your major new result rests on 1 or 2 individuals in each location, there is probably some basis to worry about over-interpretation. Especially because there are also outliers in the control group. And yet the authors imply (last paragraph of the discussion section) that we should now do population screening for this variant.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed