In this new paper, Chris Murray's team at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation reports on mortality, incidence, years lived with disability (YLDs), years of life lost (YLLs), and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 28 cancers in 188 countries by sex from 1990 to 2013. The only problem is that perhaps three-quarters of those 188 countries produce no meaningful data whatsoever on these quantities. But the figures and graphs are stunningly beautiful.

But with even mortality data so unreliable in most of the world, why go the extra strep and try to report cancer incidence? Clearly Murray’s professional strategy for getting money and attention is claiming to know everything, or at least being able to provide a number for everything. Thus, it would not serve him to publish something more restrained or conservative. Others could do that, but his unique forte is the chutzpah to assign a number EVERYWHERE for EVERYTHING. And he also knows that he will never be held accountable for these numbers, so what does it matter to him if he is off by a factor of 2 or even a factor of 10? His strategy is wildly successful, especially with powerful benefactors such as Bill Gates and Richard Horton. In short, his fantastic success is due to publishing papers that overreach, just like this one.

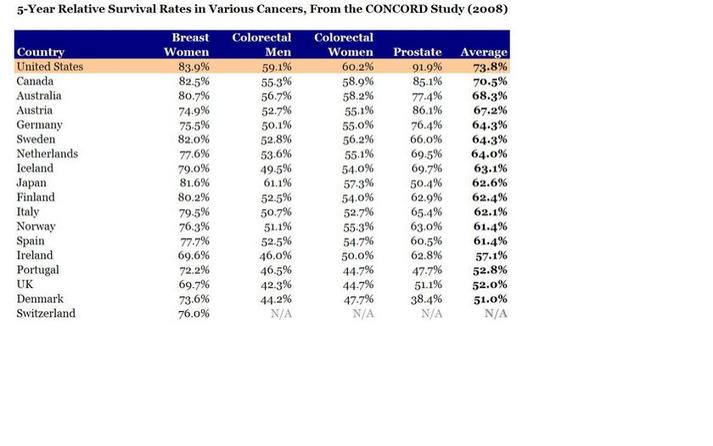

But surely the issue of cancer incidence is more complicated because any country that screens more will find more cancers, and will therefore also lengthen the time that people spend with cancer and the number of people who ultimately die with cancer (even if not from cancer). So you can get data like these:

How does the US, which does not have the highest life expectancy by any stretch, have the highest 5-year survival for every cancer on this table? By aggressive screening of old people for a profit, which I assume is not a characteristic of the health system of any other country shown. For example, Switzerland had a 2012 age-standardized cancer mortality rate for women of 83.9/100,000, whereas for the US it was 104.2/100,000.

How does the US have such a high percentage of women surviving 5 years with breast cancer but at the same time, 20% more eventually dying of breast cancer? It has to be via finding smaller tumors sooner. In poor countries, you can have lower incidence (because of less screening) and thus lower mortality from cancer, even in the context of higher mortality overall. Therefore, lowering one’s national cancer incidence and mortality rates can hardly be taken to be a sign of success.

I therefore can’t see any value to this surveillance activity for incidence, driven as it is by arbitrary policies on case finding that don’t necessarily benefit patients in terms of costs or longevity. I think we only want to know overall life expectancy, or perhaps quality adjusted or disability adjusted survival. But not cause specific incidence. Maybe not even cause specific mortality. Certainly not for a disease like cancer that is subject to so much arbitrariness in the timing of case ascertainment.

Arnaud Chiolero adds:

I agree that 5 years survival cannot be used for the surveillance of cancer (see here). The incidence is also misleading for many cancers (e.g., breast cancer in the US), but not for all (incidence of lung cancer is coherent with smoking trends, at least for the moment; it will change when screening becomes more frequent). However, mortality rates are much less biased and trying to measure and reduce cancer mortality rates is a reasonable goal, I think (see here).

But with even mortality data so unreliable in most of the world, why go the extra strep and try to report cancer incidence? Clearly Murray’s professional strategy for getting money and attention is claiming to know everything, or at least being able to provide a number for everything. Thus, it would not serve him to publish something more restrained or conservative. Others could do that, but his unique forte is the chutzpah to assign a number EVERYWHERE for EVERYTHING. And he also knows that he will never be held accountable for these numbers, so what does it matter to him if he is off by a factor of 2 or even a factor of 10? His strategy is wildly successful, especially with powerful benefactors such as Bill Gates and Richard Horton. In short, his fantastic success is due to publishing papers that overreach, just like this one.

But surely the issue of cancer incidence is more complicated because any country that screens more will find more cancers, and will therefore also lengthen the time that people spend with cancer and the number of people who ultimately die with cancer (even if not from cancer). So you can get data like these:

How does the US, which does not have the highest life expectancy by any stretch, have the highest 5-year survival for every cancer on this table? By aggressive screening of old people for a profit, which I assume is not a characteristic of the health system of any other country shown. For example, Switzerland had a 2012 age-standardized cancer mortality rate for women of 83.9/100,000, whereas for the US it was 104.2/100,000.

How does the US have such a high percentage of women surviving 5 years with breast cancer but at the same time, 20% more eventually dying of breast cancer? It has to be via finding smaller tumors sooner. In poor countries, you can have lower incidence (because of less screening) and thus lower mortality from cancer, even in the context of higher mortality overall. Therefore, lowering one’s national cancer incidence and mortality rates can hardly be taken to be a sign of success.

I therefore can’t see any value to this surveillance activity for incidence, driven as it is by arbitrary policies on case finding that don’t necessarily benefit patients in terms of costs or longevity. I think we only want to know overall life expectancy, or perhaps quality adjusted or disability adjusted survival. But not cause specific incidence. Maybe not even cause specific mortality. Certainly not for a disease like cancer that is subject to so much arbitrariness in the timing of case ascertainment.

Arnaud Chiolero adds:

I agree that 5 years survival cannot be used for the surveillance of cancer (see here). The incidence is also misleading for many cancers (e.g., breast cancer in the US), but not for all (incidence of lung cancer is coherent with smoking trends, at least for the moment; it will change when screening becomes more frequent). However, mortality rates are much less biased and trying to measure and reduce cancer mortality rates is a reasonable goal, I think (see here).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed